Sorghum (Jowar)

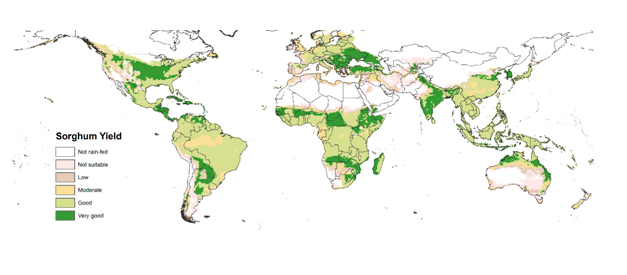

Sorghum, an important grain in many countries, is among the top five cereal crops grown in the world. The Sorghum crop can thrive in both temperate and tropical climates (because of its high photosynthetic efficiency), and under different conditions (rain-fed, irrigated, seedling transplanting or ratooning). The crop has a short maturity period and the highest food production per unit of energy spent. Post-harvest, its uses can be versatile, as the whole plant can be used in a variety of ways (staple food, animal feed, fuel) and also prepared as food in a number of ways (boiled, cracked, malted, baked, popped, etc.). But, it is mainly grown as a food crop in rain-fed semi-arid regions of India and Africa (average temperatures 27C and annual rainfall 300-700 mm. In the United States sorghum grain is primarily used for livestock feed and ethanol production and is becoming popular in the consumer food industry too. In the drier regions, it is commonly replaced by pearl millet (Africa, India) or foxtail millet (India, China), and in the wetter regions by maize. United States, India, Nigeria, Mexico, Sudan, Australia and Argentina are the important sorghum producing countries in the world.

In India, sorghum was the most important traditional staple crop of rainfed regions up to the early 2000s. It is cultivated both during the rainy kharif (June–October) and post-rainy rabi (September–January) seasons, with over 90% of production from entirely rain-fed areas. Kharif sorghum is more high yielding than rabi sorghum. Till the turn of the century, it was the country’s third most important crop after rice and wheat. India was also the second largest producer of sorghum (after the United States), with the largest (11 mha) cultivated area, but the country now ranks 5th behind Mexico, Sudan and Nigeria.

In the States with greater share of cultivated area under rainfed agriculture, like Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh/Telangana, Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, sorghum farming contributed significantly to the State GDP. However, with rapid growth of economy and consumer incomes from late 1990s, consumer food preferences began to shift to rice and wheat as major staples, and farmer preferences shifted to growing more commercial crops like soybean, cotton and maize. In parallel with global trends, the area under sorghum in India also declined from over 18 mha in early 1960s to about 4 mha in recent years. However, in the past several years national and global interest in sorghum has been rejuvenated after its repositioning as a unique ‘smart crop’ – ‘food smart’ (nutritious gluten free cereal with higher protein), ‘water smart’ (higher water use efficiency), and ‘climate smart’ (capable of adapting to varying drought conditions), and ‘energy smart’ (as a potential source of ethanol/biofuel).

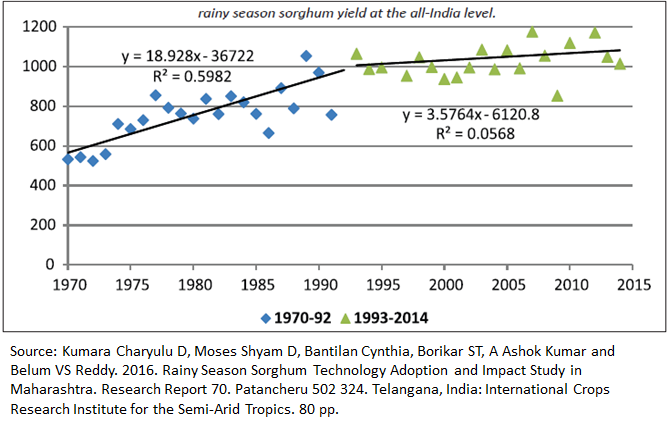

The spread of modern hybrids and varieties of sorghum in India began in the late 1960s, with the release in 1964 of the first high yielding hybrid CSH-1 developed by Dr N Ganga Prasada Rao, and the equally high yielding variety Swarna in 1968, also developed by him. Both resulted in quantum jumps in yield (up to 4-5 tons/ha) compared to the traditional varieties of the time (0.3 to 0.5 tons/ha). Varieties have the advantage that farmers’ can reuse the grain they produce as seed, where as hybrid seeds are commercially bought from seed producing companies every season as their grain output cannot be used as seed for next crop. Developing a variety that yields the same as hybrid was a historical first in plant breeding in general and gave even small farmers access to the same level of new technology.

CSH-1 and Swarna marked the advent of green revolution in dryland or rainfed agriculture (on the lines of wheat and rice for irrigated agriculture), and the launch of a systematic sorghum breeding programme in India to sustain the green revolution under the aegis of the All India Sorghum Improvement Project (AICSIP). Dr Ganga Prasada Rao was the National Coordinator of the Project from its inception in 1961 to 1978. During this period nine hybrids (CSH-1 to CSH-9) and eight varieties (CSV-1 to CSV-8R) were developed with improvements in productivity, pest and disease resistance, grain quality and other traits of economic significance. The programme also led to India becoming a unique centre of origin for the post-rainy (rabi) season varieties of sorghum.

The new hybrids and varieties spread to occupy over half the cultivated area under sorghum in the country by 1990, and nearly the entire rainy (kharif) season area by early 2000s. The Project also laid the foundation for development of efficient seed industry, first in the public sector, followed by gradual inclusion of the private sector from the 1980s. In addition to increased overall production levels in sorghum growing states of India, the substantial yield gains with the new hybrids and varieties had a significant nationwide impact by lifting millions of small dryland farmer families out of poverty and improving the quality of life in their households.